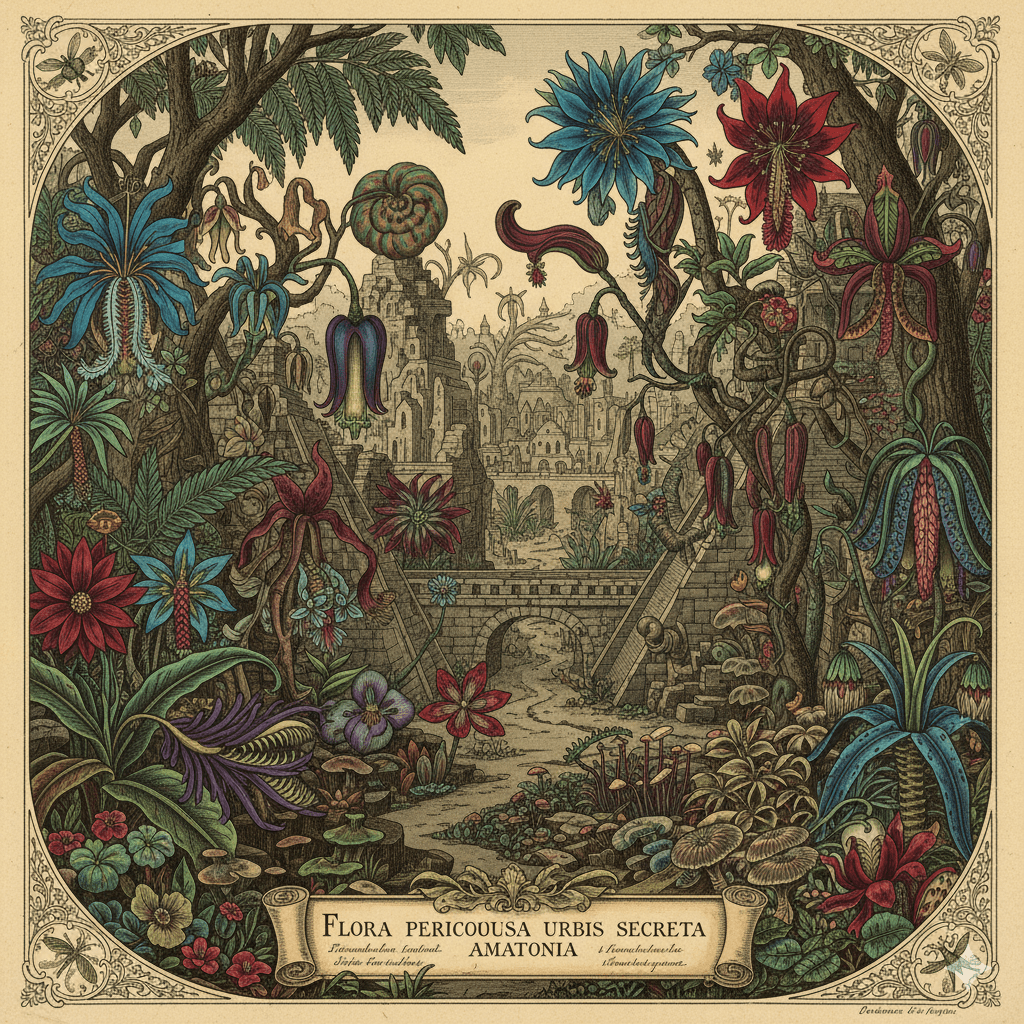

There is a moment, the first time you use it, that feels like witnessing a miracle. You type a clumsy phrase – a lost city in the Amazon jungle, overgrown with impossible flowers, in the style of a 19th-century botanical illustration – and the machine obeys. In seconds, an image blooms on the screen, more perfect than you had imagined. The script you were struggling with writes itself. The code you were stuck on is untangled. The feeling is one of immense, frictionless power. But then, a quiet dissonance begins to creep in. You look at the image, and something is off in the shadows. You read the script, and a strange, hollow repetition echoes in its rhythm. You stare at the work, this polished and plausible artefact, and a chilling question surfaces: did I do that? This anxiety is not, as is often claimed, about telling “real” from “fake.” That is a shallow problem of verification.

The true crisis of the generative age is a quiet, creeping atrophy of our capacity for judgment, the hollowing out of a uniquely human skill. This is not a threat to what we know, but to how we know. This essay is an argument that human judgment is a muscle, a form of skilled, practical wisdom that is built only through the friction of a resistant world. The seamless, effortless outputs of generative AI are the cushioned walls of a sensory deprivation tank for the human will, and by embracing them, we are choosing to forget how to walk.

I. Judgment Forged in Resistance

To understand the limb we are so eager to place in a cast, we must first understand how it works. What is this faculty we call judgment? It is not merely information. You can read every book on naval architecture—memorize the tensile strength of steel, the principles of hydrodynamics, the history of shipbuilding—and you will possess a vast store of propositional knowledge, of Ryle’s ‘knowing that.’ But this will not, by itself, grant you the ability to guide a ship through a storm. That ability, that intuitive, adaptive, and intelligent practice, is a form of ‘knowing how.’ It is a skill woven into the mind through repetition, failure, and correction.

You know how to ride a bicycle not because you can recite all the physics, but because you carry the memory of falling in your bones. Judgment is the highest order of this skill. It is the seasoned physician’s ability to diagnose a rare disease from a constellation of ambiguous symptoms, the jurist’s capacity to apply legal precedent to a case unlike any seen before, the artist’s eye for when a single brushstroke is needed to bring a canvas to life. In every instance, a body of ‘knowing that’ is present, but the judgment itself is in the masterful, uncodifiable application: the how.

So, if judgment is a skill, how do we learn it? Where is the gymnasium for the soul? I found my answer in the frustrating glow of a computer screen late at night, years ago, trying to learn how to code. No textbook could teach me the intuitive feel for why a program was breaking. That knowledge came only from the agonizing, formative hours spent hunting for a single misplaced semicolon that was crashing the entire system. It was the stubborn, infuriating resistance of the code itself, its absolute refusal to bend to my intentions, that taught me the deep logic of the machine. The triumph was not in getting the program to run, but in the person I had to become to make it happen: more patient, more meticulous, more attuned to the subtle interplay of cause and effect. This is the pedagogy of resistance.

Matthew B. Crawford argues that this struggle against a non-compliant reality is the primary mechanism for cultivating intelligence. The novice carpenter learns the soul of wood from the visceral feedback of the grain splitting under a poorly aimed chisel, as opposed to from a manual. The scientist learns the shape of the truth not from a hypothesis, but from the data that stubbornly refuses to fit. This struggle is the entire point. It is the whetstone that sharpens the blade of our discernment. Generative AI, in its very essence, is engineered to eliminate this sacred resistance. It offers a world without grain, a world where the wood never splits, where the code never breaks, where a plausible answer is always a click away. It presents itself as a liberator from the struggle, but what it is actually offering is liberation from the self we might have become.

This is where we are met with the most seductive argument in favor of this new world: that AI just reallocates effort from low-value drudgery to high-value creativity. Let the machine summarize the tedious articles, write the boilerplate code, check the grammar, so that we, the human agents, can focus on grand strategy and visionary synthesis. This is a powerful and comforting lie. It rests on a fatal misunderstanding of how mastery is built. It imagines that a complex skill can be neatly disassembled, its “drudgery” outsourced, leaving behind a pure, refined core of “creativity.”

But in any meaningful craft, the two are inextricably linked. The “tedious” process of a historian meticulously cross-referencing primary sources is the very activity through which that judgment is forged. The “drudgery” of a programmer debugging line-by-line is not an obstacle to be removed from the act of engineering; it is the primary means by which they develop a deep, intuitive feel for the system. By outsourcing the parts of a process that demand sustained, focused, punishing effort, we remove the formative practice. We are repositioned from practitioners, our hands dirty with the substance of our work, to spectators, or at best, managers of a black box. The effort is indeed reallocated, but it is a reallocation away from the foundational struggles that build ‘knowing how,’ toward the superficial curation of a machine’s vast, un-owned repository of ‘knowing that.’

II. The Ghost in My Machine

The precise mechanism of this deskilling can be understood through C. Thi Nguyen’s haunting concept of “value capture.” Nguyen describes how our engagement with a rich, complex, and often ineffable value can be hijacked by a simplified, legible, and quantifiable proxy. The deep, intrinsic value of “getting an education,” for instance, is captured by the simple metric of a grade point average. Our behavior then shifts to optimize for the proxy (cramming for the test) rather than engaging with the original, richer value of genuine understanding. Generative AI is the most powerful engine for value capture ever invented. It takes the profound, intrinsically valuable, and deeply personal process of “developing judgment on a topic” (a ‘knowing how’) and replaces it with a simpler, clearer, more efficient proxy goal: “producing a document that has the formal properties of a well-judged analysis.” Our values are captured by the affordances of the tool. The goal is no longer to become a better thinker, but to produce a better-looking thought-product, instantly.

This initiates a subtle but devastating alienation from our own minds. When I use a generative tool to help write an argument, an ambiguity infects the process. Is this sentence, this turn of phrase, this intellectual connection, genuinely my own, birthed from my unique history and effort? Or is it a clever, statistically probable echo from the machine’s training data, a ghost from the vast digital graveyard of other people’s thoughts? This ambiguity corrodes the sense of earned intellectual ownership that is the primary reward for difficult cognitive work. It robs us of the irreplaceable feeling of making something with our own minds. The skill we begin to cultivate is the thin, procedural ‘knowing how’ of manipulating a particular piece of software. We become expert prompt engineers instead of expert thinkers.

This leads directly to the functionalist’s cold, soul-crushing objection: who cares? If the final output is indistinguishable from, or even superior to, what a person could produce through struggle, what is the loss? If a student produces a more coherent essay on Kant using an AI assistant, isn’t that a better educational outcome? This argument sees all human activity as a problem of production. It views the human mind as a clumsy, inefficient factory, and the essay as just another product on the assembly line. It is a logic that is blind to formation.

The entire purpose of asking a student to write that essay is not to add another mediocre document to the world’s infinite library of Kantian commentary. It is to force that student through the crucible of a cognitive process: the struggle of research, the frustration of synthesis, the terror of the blank page, and the slow, dawning clarity of articulation. The essay is merely the scar tissue from that formative wound. To outsource the process is to abandon the entire pedagogical and humanistic project. To value the AI-generated text as equal to the human-authored one is to commit a category error of immense proportions. It is to say that a perfectly replicated, 3D-printed Stradivarius has the same value as the original, ignoring the history, the craft, the soul embedded in the wood by a human hand. One is an artifact of pattern-matching; the other is an index of a mind’s intentional, effortful, and beautiful struggle to bring order to the world.

III. The Politics of Passivity

This degradation of individual judgment is a political catastrophe in the making. The subject being cultivated in this new environment of frictionless, plausible outputs is a subject uniquely ill-equipped for the brutal, practical demands of democratic citizenship. A healthy democracy is a messy, grinding, collective practice of self-governance. And citizenship, at its core, is a form of ‘knowing how.’ It is the practiced skill of listening to those with whom you passionately disagree, the hard-won ability to evaluate the credibility of a source, the wisdom to weigh competing arguments, and the fortitude to hold power accountable. These are not innate virtues; they are skills that atrophy from disuse. The environment of generative AI pours a corrosive acid on the very foundations of this practice.

First, it creates an unsustainable cognitive burden that leads to an epidemic of exhaustion. When any email, news report, social media post, or video can be a frictionless, photorealistic fabrication, the task of verification becomes a constant, draining, full-time job. The rational human response is not to become a hyper-vigilant forensic detective, but to simply disengage. We retreat into a shell of generalized cynicism, a state of learned helplessness where the effort required to distinguish truth from fiction becomes too costly to bear. This is the death of public reason. A functioning democracy depends on citizens exercising the skill of distinguishing serious argument from bad-faith noise. An environment that makes this practice prohibitively difficult dissolves the shared ground of reality necessary for debate, leaving only the raw, tribal allegiance of the informationally shell-shocked.

Second, the constant habituation to frictionless, optimized, and personalized solutions cultivates a deep and dangerous intolerance for the messy reality of democratic processes. Democracy is, by design, full of friction. Its core components – deliberation, checks and balances, compromise, procedural justice – are intended to be slow, difficult, and frustrating. They are features, not bugs. They are the institutional brakes designed to prevent a society from careening off a cliff of popular passion. But a citizenry being technologically conditioned, like a rat in a cage, to expect instant, seamless solutions will inevitably view the hard work of democracy as an intolerable system error. This procedural intolerance creates fertile ground for the authoritarian strongman who promises to sweep away the gridlock and the endless debate to just “get things done.” The difficult ‘knowing how’ of politics is replaced with the seductive, smooth efficiency of executive command, and we cheer for our own disenfranchisement because it feels so much more convenient.

This is where the final objection from the techno-optimists appears: that AI will not create passive subjects but will empower a new generation of hyper-informed citizens, armed with tools to analyze legislation, fact-check politicians in real time, and level the informational playing field. This vision is a dangerous illusion. It ignores the brutal logic of the political economy that drives this technology. While such empowering tools might exist in niche corners, the dominant commercial applications of generative AI are overwhelmingly engineered for passive consumption.

The business models of Silicon Valley depend on capturing and holding our attention, and that is most easily achieved through frictionless, entertaining, validating, and pacifying content. The informational weather system will be structured to foster passivity. More importantly, this vision makes the cardinal error of confusing access to information with the possession of skill. You can give a person a library of every great book on surgery, but that mountain of ‘knowing that’ will not grant them the ‘knowing how’ to perform an appendectomy. The skill of political judgment, like surgery, requires practice. An environment that systematically disincentivizes this difficult practice by offering easy, plausible answers will cause that skill to wither on the vine, no matter how much information is theoretically at our fingertips.

Conclusion

The crisis of our generative age, then, is not that we will be tricked by fakes, but that we will willingly de-skill ourselves into obsolescence. We are becoming like machines: processors of input, generators of output, with no struggle, no soul, and no judgment in between. The threat is the erosion of the human capacity to skilfully and intentionally engage with a resistant world. I have argued that this occurs through a systematic substitution, a form of value capture where the difficult, formative process of building ‘knowing how’ is replaced by the frictionless production of artefacts that merely simulate ‘knowing that.’

What, then, must we do? The resistance cannot be primarily technological; it must be ethical, pedagogical, and deeply personal. It is the conscious, deliberate, and sometimes painful choice to re-valorize difficulty. It is the decision to seek out friction, to embrace the resistant mediums that forge our skills, whether that medium is a block of wood, a line of code, a difficult text, or a conversation with an adversary. In an age offering the seductive ease of infinite, disembodied knowledge, the most vital and rebellious human act is to insist on the difficult, embodied, and effortful practice that constitutes real understanding. To surrender that struggle is to surrender the very thing that makes us agents in our own lives.

References

Crawford, M. B. (2009). Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work. Penguin Press.

Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Games: Agency as Art. Oxford University Press.

Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press.

Leave a reply to Ed Podesta Cancel reply